Latest revision: October 29th, 2024.

Objective

The objective of this essay is to provide a conceptual discussion on the teleology of natural evolution. All arguments made will be in attempt to substantiate a single claim: that inherit to evolution is an intrinsic telos. This essay will first lay out Aristotle’s Four Causes, which are central to defining the telos of a process like evolution, as well as for distinguishing telos from other aspects of a process such as its function or change and exterior arbitration. Importantly, this essay will examine the nuances of teleology, such as the discrepancy between intrinsic and extrinsic telos, and will invoke famous debates, such as those of Aristotle and Democritus, Richard Dawkins and creationists (though, this is not a evolution versus creationism debate by any means), and specific examples and scenarios of evolution which examine the purgatorial function of evolution as a reified process, the arbitration capacity of environmental pressures, the necessity of telos in producing desired outcomes (especially in instances of evolutionary “jumping” or convergent “cobbling”), and where specific emphasis must be placed in determining each of these.

Table of Contents

CHAPTER 1: ARISTOTLE AND THE EFFICIENT & FINAL CAUSES

Ch.1 Part A: Introduction, Terms, & Parameters

Ch.1 Part B: The Debate on Teeth

CHAPTER 2: EVOLUTION AS A TELEOLOGICAL FAITH, & PERSPECTIVES

Ch.2 Part A: Phenomenology & The Bronze Age Critique

Ch.2 Part B: Frames of References

CHAPTER 3: PERSPECTIVE FOUR: THE GUIDING HAND

Ch.3 Part A: The Laryngeal Nerve Debate

Ch.3 Part B: “Cobbled Together” & the Tsetse Fly

Ch.3 Part B - Segment I: Convergent Evolution & Evolutionary “Jumping”

Ch.3 Part B - Segment II: The Tsetse Fly

Ch.3 Part C: Implications - Tying it All Together

END NOTE

Chapter 1: Aristotle and the Efficient & Final Causes

Chapter 1, Part A: Introduction, Terms, & Parameters

Is evolution teleological? For those unfamiliar, teleology is the study of “telos”, which refers to the purposeful ends or final cause of an object, act, or system. The question this essay seeks to answer then is whether natural evolution as a function of nature can be said to purposefully tend toward certain ends, as opposed to the secular view which holds that evolution is a result of accidents lacking any intrinsic purpose or sense of direction. Most simply—but without reducing the question to a bare three words—we can phrase the question as thus: “Is there a final cause of evolution?”

I find that secularists, by which I mean secular or irreligious atheists, are the primary crowd which would take the “naysayer” position and deny a teleology to evolution when presented with the question directly. (This is not to say, however, that secularists implicitly believe or treat their approach to evolution in a manner of accidentalism—in practice, many do not, which is something that will be explored in the second chapter.) Nonetheless, let us begin by dealing with the question of this essay directly.

Before we can begin this discussion, let us first examine four crucial terms. Aristotle identifies four “causes” for any given thing: First, there is the material cause, which refers to that which composes a thing. Then there is the formal cause, which refers to the form taken by a thing. These two can be associated with the “what” of something. Next is the efficient cause, which refers to that which transforms a thing or system, often invoking change and motion, and is associated with something’s creation and function or operation—its “how”. Finally, there is the final cause (pun intended), which is synonymous with the Greek term “telos” (τέλος). It is associated with the “purpose” of a system—its “why”—, concerning what ends a thing moves towards and “for the sake of which a thing is done”.

To help us understand this, a classic example is presented of a table:

Here, we see that the material cause of the table is wood, the formal cause is the defining shape of this three-legged table, its efficient causes are the carpentry work which was invested into its creation and the act of standing that the table performs, and the table's final cause is its purpose in being used for dining (or perhaps for other purposes, such as holding vases for decoration). Another example that I particularly find useful is that of a human organ, since there is sometimes debate as to whether the function of the organ is the same as its purpose, or whether the organ even possesses a notion of “purpose”. Aristotle’s Four Causes will help us to solve this problem. Let us take the liver, for instance: A liver’s material cause is primarily epithelial tissue, its formal cause is its iconic bean shape, its efficient causes are its development as an organ and the metabolism of chemicals that it performs, and its final cause is the detoxification of blood. Aha! So here we begin to see the merit in the final cause: The liver metabolizes chemicals, but for what sake or what end? To detoxify the blood! We have thus found that there is a distinction between its efficient and final causes—between its function and purpose. (As an unimportant side-note, it might be noted that if the liver encountered an unusual chemical which it was not designed to handle, such as methanol, and then converted it into a toxic metabolite, in this case methanoic or formic acid, this would be antithetical to its final cause of detoxifying the blood. In this case, we can say that the liver has failed to satisfy its “original” or “preordained” final cause. However, I do not believe that there is a scenario where evolution as a process fails to achieve its final cause. Even if a species becomes extinct due to failure to quickly adapt, evolution has still met its final cause of producing fitter forms by elevating the collective genetic integrity of all existing or extant species, since it has purged those which were “dysgenic” by comparison.)

In the context of evolution, we might say that the material causes are genetic mutations, epigenetic changes, gene duplications, gene deletions, and the introduction of new genes. The formal causes, meanwhile, would be the physical and phenotypical consequence of these mutations—the physical rendition of the creature’s form and its appearance. For instance, if we imagine a fish which has a “defective” genetic mutation that causes its eyes to not function correctly, we might say that the formal cause taken by this genetic mutation is the resultant blindness and the appearance of pale eyes. Now, while some might say that epigenetic theory invokes discussions surrounding the validity of Lamarckian evolution (I would argue that it does and am myself a supporter of Lamarckian evolutionary theory on this basis), these first two categories (the material and final causes of evolution) are relatively uncontroversial for the most part. It is in discussions of the latter two causes (efficient and formal) which give way to intense controversy:

The efficient cause of evolution—that is, what “drives” its operations, so to speak—is typically relegated to “environmental pressures”. Although, I prefer to demonstrate nuance here and say that evolution is its own efficient cause, while environmental pressures assume a role of “arbitration”, “deciding” who is fit or unfit and must conform to pressures, as we will see later. Meanwhile, the final cause of evolution would be the actual production of a fitter organism—the culmination of its “efforts”. I would argue that the efficient and final causes are inherently intertwined, such that the efficient cause is always working or aiming toward the final cause, as per Plato’s assessment (as will be discussed later). This is in recognition that environmental pressures (as the arbiter of evolution) intrinsically “demand” something of their inhabitants, while evolution itself purges those which do not conform to these pressures. For instance, if a species finds itself in an environment that is increasingly becoming hotter and drier with time, then we might say that there is an “ideal” fitter form of this species, which requires less water and is more heat-tolerant, and which the existing iteration of the species must “climb towards”. And here, it is the environment itself which, in a sense, “demands” this transformation or evolution through the pressures it “exerts”, while evolution as an actual process purges those unconforming to said demands.

Of course, this is the point where an accidentalist will excuse me of reifying the environment, imagining that “Nature” has a “Will” of its own—a sort of quasi-destiny with a preconceived end in mind which it has predisposed this species toward. However, my position concerning any “Will” exerted by “Nature” is that it, as Aristotle argues, “exhibits functionality in a more general sense than is exemplified in the purposes that humans have.” This is in light of recognition of the distinction between “intrinsic” telos and “extrinsic” telos: Extrinsic telos are those possessing a degree of “deliberation, intention, consciousness, or intelligence”, such as human inventions which are designed purposefully in the sense that they are made with a specific function to fulfill in mind (think specialized tools, machines, shelters, and so forth). This is contrasted with intrinsic telos, which forego the notions of “deliberation, intention, consciousness, or intelligence”. It can be confusing, however, trying to understand how “purpose” might exist in the absence of some superimposed, extrinsic, and possibly-Divine “Will”. Really, however, this demonstrates, more than anything, the failure of translation to capture the nuances of a word’s original meaning. The word “telos”, again, comes from Greek, and in English it is best translated as “end” or “aim”—the final cause. What intrinsic and extrinsic telos are really both seeking to answer then, is the same question: It is the earlier question invoked of “For what sake is a thing done?”.

Discussions on the telos or final cause of a system, then, does not necessarily invoke a superimposed extrinsic Will of any sorts, but merely begs the question, “Why does the system act, arise, or condition in this way, and how does this pertain to its ends?” Moreover, when we speak to terms like “Will” or its synonyms “agency” and “volition”, what we are really getting at is just an “aboutness” to things (that which, again, “exhibits functionality”, according to Aristotle), such that we might think of how creatures which lack a developed consciousness, and which therefore also lack any capacity for exercising deliberation (which is to say that they lack an extrinsic volitional capacity), such as perhaps primitive mollusks, jellyfish, plants, or any other creatures lacking a brain or complex nervous system, are still capable of “seeking out” sunlight, warmth, shelter, nourishment, and reproduction. This understanding that Will, agency, or volition only concerns an “aboutness” to things or a “functional exhibition”, will be important to keep in mind as we consider evolution as a reified “Specter of Darwin” or “conduit of death”, or as we consider environmental pressures to be an “arbiter” of nature that intrinsically “imposes demands” upon its inhabitants.

In fact, it is worth noting that Aristotle actually makes the case that applying telos to natural processes does not necessitate an Intelligent Designer. According to him, the notion that there is an Intelligent Designer is “absurd” because of the lack of a visible “deliberating” in nature. He explains in Physics, 2.8, 199b27-9: “It is absurd to suppose that ends are not present [in nature] because we do not see an agent deliberating.” While I disagree that the notion of an Intelligent Designer is “absurd”, that discussion is reserved for talk centered on theology, not teleology with respect to biology. The reason, then, that I have included this quote, is ultimately to assure accidentalists that the discussion of the teleology of evolution does not have to take a religious route. (Although, religiosity in regards to the teleology of evolution will be discussed later on where strictly appropriate.)

Perhaps at this point it is also worth noting that I would argue for teleology behind all processes, both natural and artificial—both intrinsic and extrinsic. However, my specific emphasis with this essay is on the topic of evolution, as it is sequential and tends perpetually toward order and rising action, separating it from many other natural processes which are cyclical, such as the birth and death of cosmos or even the formation and dispersion of storms. Evolution, in my opinion, has a much stronger causal nature, so to speak. It is a system of gain, hence its name “evolution”. Species, over the course of their evolutionary transformations, gain genetic material; and the organization of their bodies increases, as new varieties of tissues and organs come about with their own specializations, accompanied by an increasingly complex physiological and anatomical ordering of such tissue and organ systems. While some offshoots of the evolutionary tree may defy this norm, the overwhelming standard is that of gain rather than loss, of evolution rather than devolution: More genetic material is gained across the sum of all lineages than is loss, more functions and specializations are acquired than ceded, and general complexity and order typically increases rather than decreases. That evolution is subject to a linear growth rather than the typical cyclical nature of most other natural processes, I find it impossible to say that it is by any means deprived of telos. After all, how could it not be dispensed toward some final cause if its efficient cause might run contrary to the natural standard?

For fear of agitating the accidentalists, I must again assert that what I am implying here is not a “willful” or extrinsic process. I am mostly in agreement with Aristotle: Even as I am somebody who is religious, I view all natural processes (despite considering them to be “creative”) as “automatic” functions. That is to say, “creation” is automatic, “generative”, or even “procedural”, rather than willfully and intentionally architecturally construed. To me, the “Divine Architect” is ontological motion itself—the “engine” that “drives” all potencies to translate to a state of act. This is in light of the fact that in the monistic philosophy that I subscribe to, that God at the most Absolute degree is “beyond” any “conditioning” or quality. That is, God is beyond Will itself, in the conventional sense of Will as existing with respect to conditions, conditioned phenomena, or conditionality. As an emanationist, I would say that Reality simply emanates from God, spilling out of Him like an endless fountain, so to speak. (See my Finding God in the Void essay.) Even the seemingly “architectural” constructions of animals might be categorized this way, as automatic and as possessing only an intrinsic telos, since they seem devoid of actual deliberation. Think of how a beaver kept as an indoor pet will still seek to construct “dams” of random objects, even with no access to wood or running water against which to impose that which a dam is ordinarily constructed in light of (the dam’s final cause). The beaver will do this even when it has never seen or built a proper dam, and even when deprived of the opportunity to be trained in the ways of dam-building. It is, for the beaver, an automatic function. Aristotle, in discussing the concept of final cause, explains:

“This is most obvious in the animals other than man: they make things neither by art nor after inquiry or deliberation. That is why people wonder whether it is by intelligence or by some other faculty that these creatures work—spiders, ants, and the like... It is absurd to suppose that purpose is not present because we do not observe the agent deliberating. Art does not deliberate. If the ship-building art were in the wood, it would produce the same results by nature. If, therefore, purpose is present in art, it is present also in nature.” – Physics, II.8

Socrates would go a step further than Aristotle, however. Plato provides an example in Phaedo (pg. 98-99) of Socrates sitting in a prison, wherein Plato holds that the tendons in Socrates’ legs might be regarded as the “necessary conditions” or “auxiliary causes” of his sitting—or what Aristotle would call the “material causes”—, yet there is a certain “goodness” to Socrates’ act of sitting that must explain why he was sitting as opposed to not sitting. This explanatory “goodness” is what Socrates calls the “actual cause”, akin to the “final cause” or “telos” of Aristotle.

What we are seeing here is a distinction between the ideas of “how” and “why”. One might then phrase the question of this essay as, “Why do organisms evolve?” While a religiously minded person who assents to the doctrine of natural evolution (such as myself) might be inclined to abstract about some grander telos in the ultimate scheme of things (even if that telos is purely intrinsic and the process purely procedural), the accidentalists gets right to the mundane obviosity: “They evolve to become more fit!” Ah, so then their fitter form was “better” than their previous form—it possessed a greater “goodness” to it, so to speak. Of course, I use such terms in a reified manner, but the point is clear: Organisms evolve in pursuit of a fitter condition, one which is superior relative to their present conditions. But what drives the need for this evolution? What causes it? What cause does it respond to? If your answer is “environmental pressures”, then would you not agree that it is fair to say that the environmental pressures intrinsically exert “demands” (to speak in reified manner) upon organisms to evolve in a particular way?

Of course, the accidentalists might deny that there is any actual “ideal” which evolution “strives” for, taking the stance of Democritus who “reduces to necessity all the operations of nature” (see the eighth chapter of Aristotle’s Generation of Animals). However, Socrates accuses those who do not seek out the “why” as failing “to distinguish the real cause, from that without which the cause would not be able to act, as a cause”. He says such people are “groping in the dark”, and in regards to the structure of the world, he asserts, “As for their capacity of being in the best place they could be at this very time, this they do not look for, nor do they believe it to have any divine force, but they believe that they will sometime discover a stronger and more immortal Atlas to hold everything together more, and they do not believe that the truly good and ‘binding’ binds and holds them together.” (Phaedo, pg. 99). Likewise, Aristotle, in Generations of Animals, holds that while Democritus is correct in saying the operations of nature are necessary, that “yet they are for a final cause and for the sake of what is best in each case.” (Generations of Animals, ch. 8).

The impasse we find at this debate on the teleology of evolution, then, is not whether the telos are intrinsic or extrinsic—as this presumes the telos to begin with—but whether there is a telos or “final cause” at all.

Chapter 1, Part B: The Debate on Teeth

In the eighth chapter of Aristotle’s aforementioned work, Generations of Animals, we find Aristotle attempting to refute Democritus’ disregard for final causes as playing a role in the adaptations of animals (namely their teeth) by demonstrating an intrinsic purpose as the reason for every aspect of their growth and form. The chapter only consists of a few paragraphs, so I will paste it below and then proceed with my own commentary.

With regard to the teeth, it has been stated previously that they do not exist for a single purpose nor for the same purpose in all animals, but in some for nutrition only, in others also for fighting and for vocal speech. We must, however, consider it not alien to the discussion of generation and development to inquire into the reason why the front teeth are formed first and the grinders later, and why the latter are not shed but the former are shed and grow again.

Democritus has spoken of these questions but not well, for he assigns the cause too generally without investigating the facts in all cases. He says that the early teeth are shed because they are formed in animals too early, for it is when animals are practically in their prime that they grow according to Nature, and suckling is the cause he assigns for their being found too early. Yet the pig also suckles but does not shed its teeth, and, further, all the animals with carnivorous dentition suckle, but some of them do not shed any teeth except the canines, e.g. lions. This mistake, then, was due to his speaking generally without examining what happens in all cases; but this is what we to do, for any one who makes any general statement must speak of all the particular cases.

Now we assume, basing our assumption upon what we see, that Nature never fails nor does anything in vain so far as is possible in each case. And it is necessary, if an animal is to obtain food after the time of taking milk is over, that it should have instruments for the treatment of the food. If, then, as Democritus says, this happened about the time of reaching maturity, Nature would fail in something possible for her to do. And, besides, the operation of Nature would be contrary to Nature, for what is done by violence is contrary to Nature, and it is by violence that he says the formation of the first teeth is brought about. That this view then is not true is plain from these and other similar considerations.

Now these teeth are developed before the flat teeth, in the first place because their function is earlier (for dividing comes before crushing, and the flat teeth are for crushing, the others for dividing), in the second place because the smaller is naturally developed quicker than the larger, even if both start together, and these teeth are smaller in size than the grinders, because the bone of the jaw is flat in that part but narrow towards the mouth. From the greater part, therefore, must flow more nutriment to form the teeth, and from the narrower part less.

The act of sucking in itself contributes nothing to the formation of the teeth, but the heat of the milk makes them appear more quickly. A proof of this is that even in suckling animals those young which enjoy hotter milk grow their teeth quicker, heat being conducive to growth.

They are shed, after they have been formed, partly because it is better so (for what is sharp is soon blunted, so that a fresh relay is needed for the work, whereas the flat teeth cannot be blunted but are only smoothed in time by wearing down), partly from necessity because, while the roots of the grinders are fixed where the jaw is flat and the bone strong, those of the front teeth are in a thin part, so that they are weak and easily moved. They grow again because they are shed while the bone is still growing and the animal is still young enough to grow teeth. A proof of this is that even the flat teeth grow for a long time, the last of them cutting the gum at about twenty years of age; indeed in some cases the last teeth have been grown in quite old age. This is because there is much nutriment in the broad part of the bones, whereas the front part being thin soon reaches perfection and no residual matter is found in it, the nutriment being consumed in its own growth.

Democritus, however, neglecting the final cause, reduces to necessity all the operations of Nature. Now they are necessary, it is true, but yet they are for a final cause and for the sake of what is best in each case. Thus nothing prevents the teeth from being formed and being shed in this way; but it is not on account of these causes but on account of the end (or final cause); these are causes only in the sense of being the moving and efficient instruments and the material. So it is reasonable that Nature should perform most of her operations using breath as an instrument, for as some instruments serve many uses in the arts, e.g. the hammer and anvil in the smith's art, so does breath in the living things formed by Nature. But to say that necessity is the only cause is much as if we should think that the water has been drawn off from a dropsical patient on account of the lancet, not on account of health, for the sake of which the lancet made the incision.

We have thus spoken of the teeth, saying why some are shed and grow again, and others not, and generally for what cause they are formed. And we have spoken of the other affections of the parts which are found to occur not for any final end but of necessity and on account of the motive or efficient cause.

First off, I find it highly amusing that debates on the evolutionary adaptations of animals were hosted thousands of years before naturalists and the theory of evolution ever hit the scene; more so that the debate on teeth (though today as a popular staple of creation/evolution debates) is apparently timeless. But let us get back on track. There are a few key outtakes here that I find to be profound. Most notably, Aristotle says, “Now these teeth are developed before the flat teeth, in the first place because their function is earlier…” What he speaks of here is a procedural or sequential nature to the formation of the teeth is a particular order, of which multiple reasons are then substantiated. All the reasons which he is able to substantiate for the aspects of the teeth throughout the eighth chapter culminate in the conclusion that he draws in his penultimate paragraph: “Thus nothing prevents the teeth from being formed and being shed in this way; but it is not on account of these causes but on account of the end (or final cause); these are causes only in the sense of being the moving and efficient instruments and the material. So it is reasonable that Nature should perform most of her operations using breath as an instrument, for as some instruments serve many uses in the arts, e.g. the hammer and anvil in the smith's art, so does breath in the living things formed by Nature. But to say that necessity is the only cause is much as if we should think that the water has been drawn off from a dropsical patient on account of the lancet, not on account of health, for the sake of which the lancet made the incision.”

If, however, any accidentalist reading is still unconvinced that any final cause is subsumed in evolutionary adaptations, then I urge you to wait until the third chapter. Until then, the second chapter of this essay shall focus on an examination of religious and irreligious views’ consistency with regard to whether they assent to a teleological evolution and the prominence of such an assent to the teleological by the irreligious.

Chapter 2: Evolution as a Teleological Faith, & Perspectives

Chapter 2, Part A: Phenomenology & The Bronze Age Critique

I find that typically it is not the features of animals—like the growth and formation of teeth—which takes a center stage in debates on the teleology of evolution…at least not among the general lay crowds who are not accustomed to rigorous philosophical examination and discourse. Instead, such features of animals find themselves as the focus of evolution versus creationism debates, which is interesting in that these debates presume a dichotomy between a secular non-teleological position against a position of extrinsic teleological one which anthropomorphizes the Creator and superimposes Him with the human qualities of deliberation and intent. However, as this essay is NOT an evolution versus creationism debate, we will instead be looking strictly at where the contentions between teleological and non-teleological perspectives on evolution lay, in practice.

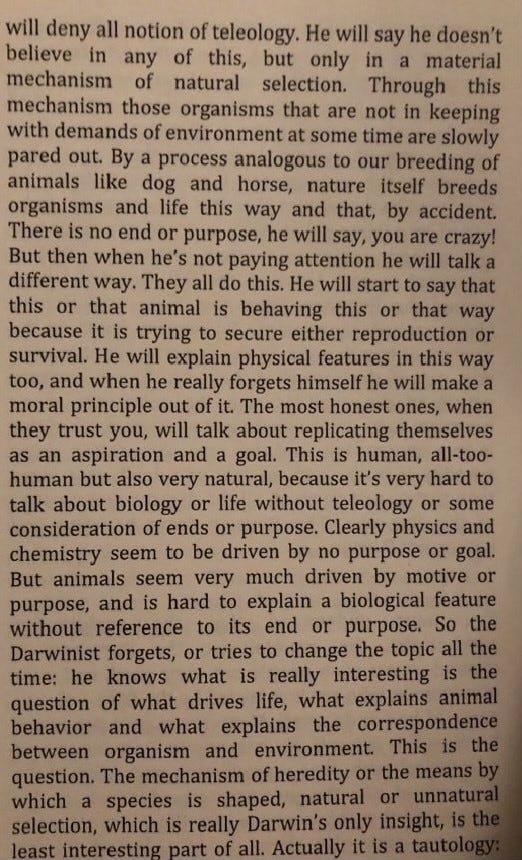

That is, rather than focusing on meta-arguments in the domain of causality which adherents to either position likely only consider when forced to examine the issue philosophically, we need to—in order for this essay to “ground” the debate—look at where the two positions would conventionally reach to justify their stances. Ultimately, I find that where a person stands typically boils down to two contingencies: Whether you believe survival and reproduction are the ends of evolution, and from what reference point you view the phenomenon. The author (his penname is rather crude) of Bronze Age Mindset, in his book, makes a good case in addressing the accidentalists who implicitly believe evolution to be teleological. The two samples from his book that I have provided photos of address those who explicitly deny that survival and reproduction are the ends of life, but will describe the process of evolution and natural selection in a way that would seem to suggest an implicit belief that survival and reproduction are the telos—to the extent that they might even moralize about it in such a fashion. See below:

(Just as a note, while the author says that Darwinists view “survival and reproduction as the ends of life”, I make the distinction that they are the ends of evolution itself. This is because, truthfully, the discussion of teleology is not about life. Survival and reproduction as ends are merely what set the genetic canvas, the basis for the conditions in which life takes place. If anything, evolution has more to do with death than life, but we will come back to this.)

In all fairness, perhaps the tendency of the accidentalists to characterize evolution in a teleological fashion is merely a means of reifying the concept in humanistic terms that are more easily related to, hence why the author says, “This is human, all-too-human”. This reification may even be unconscious, rather than any serious conviction about the phenomenology of the evolutionary process. Yet an unconscious act of reification which is so fundamental to their way of thinking that it is something which they connect to their sense of desired fulfillment in life (or personal purpose)—which is to procreate—is impossible to overlook. This desire as it pertains to personal fulfillment, is of course, transposed upon them by the ends of evolution. That is to say, they are “called” by “the Specter of Darwin” to reproduce and serve the ends of the greater phenomenon.

We find that despite the accidentalists’ attempts to deny the metaphysical, boiling everything down to materialism or physicalism, that they often cannot shake a sense of fulfilment or purpose which manifests as the desire for starting a family, for having a spouse and children. The accidentalists, however, might contend that this desire, like every emotion, in the eliminationist sense is but an illusion, reducible to some chemical reaction in their brain that natural selection has “deemed” or “found” beneficial to the survival of the human species. I have argued against eliminationism in my other essay (see the third chapter of Finding God in the Void), but that argument is beyond the scope of this topic. The point is that the accidentalists find themselves fundamentally “trapped” by telos, to the extent that we might say their mind is conditioned by it, that the telos are themselves a cause (a final cause) which acts upon them by driving them. To deny that there are telos while assenting to act under their accord, is precarious, if not outright impossible to do while remaining logically consistent and true to oneself. It is to say, “Reproduction is not the purpose of my life, yet I am commanded by a natural sense of purpose to reproduce!”

It is significantly easier, I would argue, to upload a logical consistency if one concedes to a notion of telos. Again, this is not to say that religiosity is a requirement, as even Aristotle upheld an intrinsic telos for Nature and even used this to deny that there was any “divine” designer or fashioner. Nonetheless, I will use a religious example to exemplify how easy it is for one to supply a justification should they assent to the notion of a teleological evolution:

A Christian, for instance, who believes in evolution, will by default take it to be teleological (whether intrinsic or extrinsic) and may justify this stance on the grounds of Thomas Aquinas’ notion of Secondary Causality: That is, God acting as the First Mover or self-subsistent uncaused cause, imparts upon other entities and systems the agency to act as secondary causes, whereby they may act as causes for themselves, which would mean that creation is an ongoing process characterized by a chain of causes rather than a single static event. Every natural cause in the world thus falls under this umbrella of secondary causality, including the evolution of species. For the Christian, then, a secondary cause which acts upon species, compelling them to adapt and therefore evolve, would be environmental pressures, the efficient cause behind the system, and the Christian might then follow this in saying that the resulting adaption and evolution which takes place is the “divinely willed” or “intended” final cause. The Christian ultimately believes in the guiding hand of Providence toward a planned destiny.

Really, any applied teleology to a phenomenological system which “creates” new substance (material causes, such as new genes or organs), necessarily implies Providence. Of course, this “Providence” is nothing more than a reified coupling of the efficient and final causes. Take away the religious connotation of the name “Providence”, and I see no reason as to why an accidentalist could not agree with the statement, which we can rephrase as thus: “Any applied teleology to a phenomenological system which ‘creates’ new substance, necessarily implies final causes following from efficient causes.”

Chapter 2, Part B: Frames of Reference

Continuing directly from the previous section: Yet, such discussions on reproduction as ends, and on “Providence”, only bring us back to the idea that the environment intrinsically “demands” something of its inhabitants and that the inhabiting species respond by intrinsically aiming toward the “ideal” ends: a fitter form (or formal cause). Since environmental pressures are setting-specific, the idea that the environment can impose pressures upon its inhabitants in an intrinsic manner more or less argues for a case of a conditional or context-specific teleology—a teleology with respect to the setting. And by invoking teleology with respect to a particular environmental setting, we open the door to another contingency—one which emphasizes the “angle of perspective” problem, which concerns one of four possible angles from which the evolutionary process can be viewed, as will be discussed in this section and the next. This connection is drawn in realizing that the first contingency (of environmental demand) only concerns itself chiefly with conventionally “evolved” features as opposed to “devolved” features—features which would seem to be a “step backward” but which were allowed to come about only because they did not hinder a species, since there was a lack of environmental pressures to thwart these traits or features. Likewise, the first contingency ascribes little emphasis to “neutral” or “extraneous” features which we might call “true accidents” in that no purely functional purpose may be ascribed to them, and yet they have managed to take precedence among a species. Such will be explored primarily when discussing the third of the four angles of perspective. So, what are the four angles? 1.) Viewing the process of evolution from the point of view of an individual creature and its own survival and reproduction. 2.) Emphasizing the species and its propagation broadly. 3.) Focusing on evolution itself as a phenomenological process. 4.) Invoking an arbiter or guiding hand—a “meta-actor”, such as environmental pressures or Providence, which acts upon individual creatures and whole species.

1.) The Individualist Perspective: If the point of view is from an individual creature, any discussion of telos could only apply to the individual’s own desire for reproduction, a discussion which might invoke Lamarckian evolutionary theory. For those unfamiliar, Lamarckian evolution is essentially a theory of hereditary epigenetics, where epigenetic changes that an organism undergoes in its own lifetime as responses to environmental changes are passed on to its offspring. For instance, we may see changes in gene expression pertaining to biochemical pathology as the consumption of certain proportions of chemical nutrients or chemical contaminant in the diet changes. These changes could also pertain to the availability of other local resources such as the amount of food, mating partners, or abundance of den-making supplies in the area, all of which will alter gene expressions relating to the animal’s behavior, desires, needs, and even tolerance of conditions—especially when speaking on climatic changes or frequency of encounters with predators or diseases. However, what Lamarck was really speaking to was the idea of an animal which achieves something in terms of strength, agility, sexual virility, or some other end that both benefits the animal and hopefully results in a change to gene expression which will then be passed down to its offspring. Yet, can we say the animal aimed for these ends with the knowledge that its offspring would inherit these advantages? Certainly not.

The animal of Lamarck at best is only striving to survive itself and to reproduce, but has no capacity to consider the viability or tenacity of its offspring, such that even a deformed creature will seek to reproduce. It is at best aimlessly sought after without any regard for the consequences.

2.) The Species Perspective: Moving on, when evolution is examined from the perspective of the species, we are forced to consider not just what the environment more or less “demands” of the species, but in consideration of traits which persist in their absence, or without the environment having either favored or forbid them but instead permitted them without apparent cause.

Where culling pressures fail without immediate consequence: While ordinarily we expect the environment to “demand” something of populations to draw them toward becoming “fitter”, there are cases where such pressures are absent. Take blind deepwater fish or blind moles, for instance. Deep underwater or underground, there is no light available to them, so those who were born with defective sight genes were able to spread their seed equally as well as those who were not blind, until the blindness trait, by chance, came to dominate the species. Now, one might say that this puts a tremendous weight on blind members of the species, who, in the absence of external culling pressures that would otherwise root out their “unfitness”, would now appear to be the sole arbiters of whether the overall “fitness” of their population will decrease. Really, however, in the present conditions of the environment, the blindness trait does not actually pose a problem. If it did, it would not have been able to spread and dominate in the first place. Therefore, to call the species “unfit” is actually an unfair characterization, since their circumstantial fitness is not impacted whatsoever.

Thus, we see that the duty of arbitration is not actually in the hands of the individual or species, but is still in the environmental pressures—or in the lack thereof. Moreover, this does not sound like the telos of evolution can be placed in the hands of the individual or species, since neither is of conscientious intent here, as the spread of these potentially unfit genes is a passive process rather than an active and intentional one. That is, just as we cannot blame one for responding to pressures that are there, we also cannot blame one for not responding to pressures that are not there. And with this in mind, we return yet again to the notion that environmental pressures (or their lack thereof) as the arbiter of change. In fact, to demonstrate the arbitration capacity of environmental changes, it can be observed that if the blind fish suddenly encountered bioluminescent predators (like anglerfish), or if the blind moles were suddenly forced back to the sunny surface—situations requiring eyesight to keep pace with environmental changes, then environmental pressures would still continue to serve the role of arbitration, with the species being prompted to re-evolve eyesight capacity through suddenly-imposed selective pressures. (In this way, “devolution” does not truly exist, since any disadvantage that a species has is accounted for, in that the species will either evolve to overcome the disadvantage or will be purged for its failure to quickly adapt. Either way, the disadvantage ceases to exist.)

3.) The Direct Evolution Perspective (or “Specter of Darwin” Perspective): Alternative to a perspective which hones in on life itself (individuals and species), however, is one which hones in directly on evolution itself, asserting that reproduction is not just a personal/individual end or an end for the species, but the end of evolution itself—and this is partially where I stand. It is in this way that we reify a “Specter of Darwin”. However, we must make clear here that treating evolution as an object, as if it were a “Specter of Darwin”, is not the same as something like Providence, as the former is the phenomenon or process in question (that is, evolution or the “Specter of Darwin” is the efficient cause) and the latter is a reification of the final cause of said phenomenon or process. In a more mystical sense, we might say that while Providence or the final causes generally “prefer” fitter forms of life, that evolution or the “Specter of Darwin” as a process is primarily a conduit a death—it is a “force” of death, purging all those unable to adapt and conform to environmental pressures. We might then imagine that this mystical Specter of Darwin holds a scythe and comes to reap all the weakest and most dysgenic of the beasts so that only those who attain to the standards of Providence excel. But then the question becomes, what would “give” this Specter reason to cull? Furthermore, does it exercise “good judgment”?

While we remain on the topic of dysgenics—and to answer the bespoke question— might we invoke pandas? Pandas are natural carnivores, possessing a digestive system which is best suited for meat, yet their tongues have lost their savory receptors, and thus can no longer taste meat, and so the pandas now munch for many hours a day on bamboo that is nutrient-poor to them. Or what of humans? Intelligence is required for our survival, yet average intelligence decreases over time (despite the increase in access to knowledge or total sum of knowledge produced) since those of lower intelligence typically outbreed those of higher intelligence. It would appear then that perhaps the specter of Darwin is somehow deprived of excellent judgment. Or, is this the case? Is it perhaps true instead that these beasts were allowed to “devolve” because of a lack of culling pressure compelling them to move toward or maintain what we would ordinarily consider to be a fitter condition? For instance, pandas have no natural predators and thus have no threat imposed over them should they consign to munching on bamboo all day, and we humans have largely separated ourselves from natural pressures that would mark our doom should we fail to respond to them with quick and efficacious problem-solving skills. It would seem then that attempts to reify evolution and make Darwin’s Ghost the arbiter are not so straightforward, as high standards of fitness cannot always be enforced and are subject to decay when environmental pressures wane. Thus, we yet again return to the conclusion that environmental pressures are the arbiter, and moreover that it is in fact Darwin’s Ghost who works for Providence, wherein Providence represents the final cause of evolution—that final cause being the production of new and fit (here, “fitter” is relative since what is considered “fit” is contingent upon the current environmental pressures) forms of life.

So, to condense the current conclusions into a simple bulleted list, we would say:

1.) Evolution (reified as “Darwin’s Ghost”) is the efficient cause.

2.) Environmental pressures are the arbiter, dictating what species live or die and how they evolve by imposing or not imposing certain “demands”.

3.) Evolution is primarily a conduit of death, hence “survival of the fittest”, since only those who were fit enough to meet the demands of the environmental pressures would be “permitted” to live rather than perish or go extinct.

4.) “Providence”, the reification of the final cause, is the end that evolution as the efficient cause is working toward, and this final cause is the production of new and [with regard to environment pressures] fitter forms of life.

Continuing: Despite the flaw in placing telos directly in the hands of the Specter of Darwin, however, we will often find that should we engage with an accidentalist in a way that our Bronze Age author describes, you will be shocked. They might make the case that the spread of dysgenic traits is somehow actually “evolution at work”! They might even say something along the lines of, “The species will become weaker BECAUSE of the lack of culling pressure! It may even become extinct, which is what happened to the dodo bird sometime after it lost its ability to fly!”—As if it were evolution’s Will or prescribed destiny that extinction should occur! They conflate the process with its final cause; they conflate the specter of Darwin with Providence! How folly, that to them the very same process which should ensure a species’ survival should betray it and lead it to extinction, as something “unfit” as opposed to “fitter”—as if the species fell out of destiny’s favor. Is evolution merely a passive conduit/force of death, or a motivated killer?

With all that, let us move on now to the next chapter where we will discuss the final of the four perspectives, that of the meta-actor, where we shall tread the waters of the extrinsic telos.

Chapter 3: Perspective Four: The Guiding Hand

Chapter 3, Part A: The Laryngeal Nerve Debate

The controversial Richard Dawkins, one of the most notable figureheads of the “New Atheism”, made a cameo on the National Geographic television network for a special where he was supposed to be investigating the evolutionary process of the recurrent laryngeal nerve. Because this nerve did not take a direct route from the brain to the larynx, he called it a “dumb design if it was one”. In a world where creation versus evolution debates have become a popular motif, you will find no shortage of naturalists criticizing the supposed imperfections of biological designs, such as David Barash’s article, Imperfect Reproductions, published in Wall Street Journal, itself a review on Jeremy Taylor’s similarly critical Body by Darwin. The irony of such assertions though, is that they are not blows to the creationists, but to those who believe evolution to be teleological. If the function of anatomical parts of critique is merely necessary, as Democritus implies, then it is as Aristotle characterizes Democritus’ implications: “Thus nothing prevents the teeth from being formed and being shed in this way”. How an organism’s anatomical features came about was accidental, after all, according to the accidentalist. They could have arisen in any alternative way, and as plenty are imperfect. The accidentalist would like to think, then, that were Aristotle alive today, he would have much difficulty in justifying the telos and perfection of such anatomical features as the laryngeal nerve.

In case you are wondering though, the reason attacks on supposedly imperfect designs are not blows to creationism is twofold: For one, how can we suppose that a Creator would not design features in a way which is flawed, given that the very operations of the universe necessitate that some systems can and do fail? Claiming epistemic access to the intentions of the mind of a Divine Architect is ridiculous. Secondly, a creationist could easily flip the table and ask, “If evolution ought to only bring about the fittest organisms, then why are there so many flawed organisms?” In this case, asking such questions as “Why would God design an inefficient path for the recurrent laryngeal nerve or teeth that decay?” and “Why would/How could an inefficient laryngeal nerve or teeth subject to decay evolve?” are in effect the same question! The debate goes nowhere!

But seeing as this essay is not a creation versus evolution debate, let us get back on track. Certainly, “poor” and “imperfect” features, which could have evolved to be better, would be tough for the teleologists to grapple with. But how true are the accidentalists’ claims? Is the recurrent laryngeal nerve—the most controversial feature due to its convoluted pathway—truly “maladaptive”? Are any of the anatomical features of critique maladaptive? Please forgive me, but the famous, or infamous, Institute for Creation Research (What the hell is “creation research” by the way?) actually has some good outtakes precisely addressing this in their article, Major Evolutionary Blunders: The ‘Poor Design’ of Our Recurrent Laryngeal Nerve. First presenting a string of arguments that are made in favor of the laryngeal nerve being maladaptive:

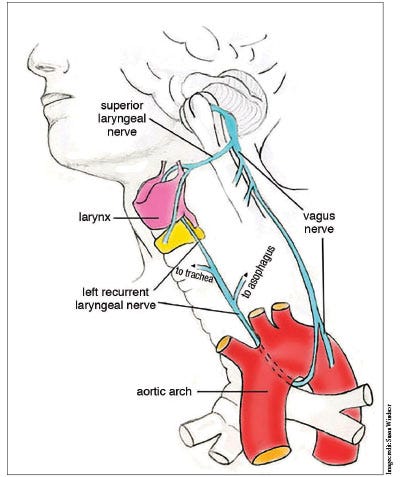

Vocal cords in the larynx are innervated by the right and left laryngeal nerves. These nerves branch off of their respective vagus cranial nerves. On the left side, the vagus nerve travels from the skull, down the neck, toward the heart, and then past it. The recurrent laryngeal nerve branches off from the vagus just below the aorta. Looping under the aorta, the RLN then travels upward (or recurs) to serve several organs as it travels up to the larynx. Evolutionists see poor design in the fact that the left nerve does not branch off closer to the larynx. (It should be noted that even though the left RLN is longer than the right nerve, signals to each nerve are adjusted so that the vocal cords are stimulated simultaneously so normal speech is produced.)

In Why Evolution Is True, Coyne affirms that “one of nature’s worst designs is shown by the recurrent laryngeal nerve in mammals. The curious thing is that it is much longer [about two feet longer] than it needs to be.” He later adds, “This circuitous path of the recurrent laryngeal nerve is not only poor design, but might even be maladaptive.”

He claims that the only reasonable explanation for the route of the nerve is that it originally started out innervating gills in fish. Later, amphibians evolved from fish and reptiles, and mammals evolved from them. Then, he says, “during our evolution” as our heart moved into our chest (unlike fish) “to keep up with the backward evolution of the aorta, the laryngeal nerve had to become long and recurrent” up to our larynx (which fish also don’t have.)

Paleontologist Donald Prothero echoes…the same assertion: “Not only is this design wasteful, but…the bizarre pathway of this nerve makes perfect sense in evolutionary terms. In fish and early mammal embryos, the precursor of the recurrent laryngeal nerve [is] attached to the sixth gill arch, deep in the neck and body region.”

Following, a rebuttal:

Scientific literature published over a decade prior to either Prothero’s or Coyne’s book detailed a very good reason why the RLN loops under the aortic arch. The RLN plays several key roles during a baby’s pre-birth development, one of which is absolutely vital and quite intriguing.

To set the stage, we know that while a baby develops in his mother’s womb, he is living in a watery world in which his lungs are not functioning for oxygen exchange. Therefore, most blood bypasses the lungs through some temporary shunts. One shunt is a small artery with a very muscular wall that connects the pulmonary trunk to the aorta. Its Latin name is ductus arteriosis. When the baby takes his first breath upon birth, the artery detects specific signals, and the muscular wall constricts in order to close the vessel. Blood is now forced into the lungs. Why does the ductus arteriosis have such a muscular wall compared to other blood vessels that have far more elastic fibers?

Investigations at Johns Hopkins Medical School found that during development, “the left vagus nerve and its recurrent laryngeal branch form a sling supporting the distal (or ductus arteriosus component) of the left sixth aortic arch.” Remarkably, these researchers found in their study that:

The media [composition of the blood vessel wall] of the ductus arteriosus beneath the supporting nerves is thinner and has less elastic fiber formation than the elastic lamellar media of the adjacent aortic arches. The study shows that the vagus and recurrent laryngeal nerves are in a position to provide mechanical support to the ductus arteriosus during its development and that the morphology [or composition] of the media of the supported ductus arteriosus differs from that of the adjacent unsupported aortic arches. It is suggested that this local mechanical support may be the reason that the normal ductus arteriosus differentiates as a muscular artery and is therefore able to obliterate its lumen in postnatal life. Without such support the ductal media could develop the abundant elastic fibers characteristic of the normal unsupported aorta and pulmonary trunk and become an abnormal, persistently patent [or open] ductus arteriosus [not a good situation].

Developmental research shows how the RLN could be seen as a wise mechanism, designed to provide the right supporting conditions during a baby’s development for the ductus arteriosus to form correctly. There are multiple purposes for this nerve beyond activating the left vocal cord. Its length, location, and function all point to ingenious—not poor—design.

As we can see here, the recurrent laryngeal nerve’s long and winding shape has a purpose, both in terms of structural support, and in terms of serving other organs along its extended path. Additionally, it is even synchronized with the superior laryngeal nerve such that the two can both send signals to the larynx simultaneously. This is not even to mention how the superior laryngeal nerve actually does take a short and straight path to the larynx—which just goes to show the dishonesty of those criticizing the recurrent laryngeal nerve, who ignore its counterpart which they would find less “maladaptive” by their own standards (not to mention how arrogant they must be in that they are not even curious as to why one should take a streamlined path while the other does not). Had Democritus and Aristotle both known about this recurrent nerve, I have no doubt that Democritus would take to being its critic while Aristotle retorted at length and provided a comprehensive overview of the organ’s final causes.

I digress, for this essay is not about the recurrent laryngeal nerve. This was merely a demonstration of a greater point: That there practically exists no feature in nature which could not be teleologically substantiated. “But what about the blind fish and moles, the carnivorous pandas condemned to eating bamboo, the flightless dodo bird, or the fact that human intelligence is dwindling?”, accidentalist might retort. Even these might be substantiated: When an organ or trait becomes vestigial, such as the eyes of blind deepwater fish, supplying energy to that organ is wasteful. It is more efficient and sustainable for the fish that the calories it consumes should be devoted to functions which actually remain in use and which are presently useful to the fish’s survival under ordinary conditions. Meanwhile, blind moles actually have the “capacity” for sight; their epigenetics have simply “turned off” the associated gene due to its non-use. Theoretically, they could regain sight in just a couple of generations if forced to revert to surface life. (Lamarck vindicated?) Concerning the pandas, why bother hunting for prey which can flee when bamboo is virtually omnipresent? Clearly, the vegetarian lifestyle is more conducive to the panda’s survival, else those who rejected tasteless meat would have been bred out of existence long ago. The dodo, on the other hand, is hard to speak of since it has gone extinct, but we might say that its grounded lifestyle was conducive to good living in the same way that the penguin or ostrich’s is, and that the dodo merely did not have enough time to respond to a sudden change in the environment’s demands. Whether one could call this the dodo’s “destiny” is tenuous, but for the teleologist it is a demonstration of a failure to attain to the desired final cause: the “ideal” fittest form. (I will let you draw the parallel here with my discussion on the ego-ideal and objet a in the first chapter of The Paradox of Transgenderism.) Humans somewhat can relate to aforementioned: Like the pandas, we have somewhat separated ourselves from many natural pressures; we thus, like the blind fish, no longer need for most members of our species to have a particular trait to devout energy to (in this case, brain power); and like the dodo, this may eventually catch up to us.

Chapter 3, Part B: ”Cobbled Together” & the Tsetse Fly

>Ch.3 Part B – Segment I: Convergent Evolution & Evolutionary “Jumping”

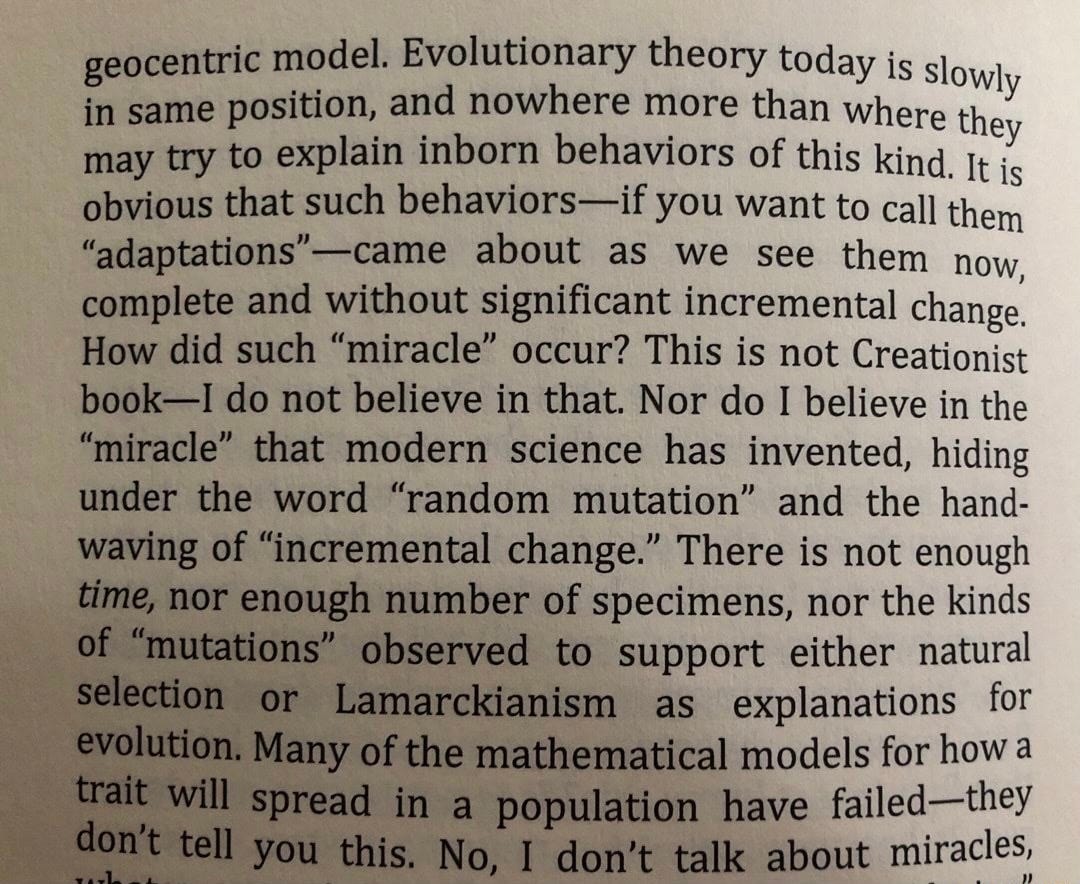

I will begin this part of the chapter with another outtake from Bronze Age Mindset:

Evolution, in essence, “cobbles together” organisms (as the ICR puts it). They are (as the above outtake reads) “complete and without significant incremental change”. While this sounds like a critique of evolution, it does not have to be if we assent to the notion that there are preconceived ends (final causes, telos) which species are working toward, even if automatically (intrinsically) as opposed to consciously (extrinsically).

(Though really, a synthesis of positions is possible. For instance, I believe as those of the Dharmic faiths do, that Consciousness is the content and function of all matter, and that we can see features of consciousness present in the behavior of all things. Even mundane physical events, such as the collision of asteroids into a planet, appear to behave in a manner which is “guided” (in the sense that these events are predicable, repeatable, conditioned, and “obeying” physical laws), “autonomous” (in the sense that they are “self-driven”, following a natural course of ontological motion set in place wherein acts arise from potencies, decay back into potencies, and so forth), and teleological (in the sense that there is a final cause which every event appears to have at its end; in this case the asteroids are helping a planet form by accreting mass). Yet this “consciousness” behind physical events is not like that of a mind which deliberates; it is still automatic. Any perception of “intent” or “volition” therein is really an “aboutness” to things. One might look, for example, to the “aboutness” of wind and observe that it is directional and “motivated” (in that it comes from somewhere and is compelled by other forces), and leads to further conditions. An anonymous teacher of mine is quoted on this matter: “A rock or even basic features of nature like wind may have attributes of behavior like intent, or seemingly have some ‘aboutness’ to them, but it would be highly unlikely that the wind itself has authentic volition or otherwise a sense of me-ness in respect to other aspects of mundane nature.” Overall, “Creation” is really just “doing its thing” so to speak. (See my Finding God in the Void essay for more of this type of discussion.))

To give some examples of organisms “cobbling together”, let us consider the strict dichotomies we observe between reptiles and mammals. Reptiles and other tetrapods have a urinary tract which merges with the lower end of the GI tract, such that their stool contains the features of urine. At the same time, mammals are the only chordates which not only separate their liquid waste but release it from the genitals rather than the anus. Meanwhile, some birds combine both their point of waste excretion and their genitals into a single cloaca. There is no transitory way that the system possessed by reptiles could have gradually morphed into the system possessed by birds or especially mammals. What the transition between asexual cloning and sexual reproduction with haploid gametes, or the transition between multicellular colonies in which each cell reproduces independently and true multicellular organisms which reproduce as a whole, looked like, is also never made clear in any of the available literature. Evolution sometimes “jumps” in a fashion so drastic and complex that it is outright unnatural and would require at times a “guiding hand”, so to speak. Convergent evolution arguably demonstrates a similar providential effect. To quote the ICR: “Other evolutionary researchers claim that ‘the discovery that the hemoglobins of jawed and jawless vertebrates were invented independently provides powerful testimony to the ability of natural selection to cobble together similar design solutions using different starting materials.’ It appears that even though nature cannot exercise any detected agency, the minds of selectionists readily project onto nature incredible creativity and resourcefulness.”

>Ch.3 Part B – Segment II: The Teste Fly

The most striking example, to me however, of any such “jumping” is that of the tsetse fly. Among its bizarre features which set it apart from other flies, such as the production of milk for its offspring and the ability to give live birth—a convergent evolution that this distantly-related insect curiously shares with mammals—are a pair of features which pertain to its reproduction: Firstly, tsetse flies, by giving live birth, can only produce a mere ten offspring in their entire life, which is orders of magnitude less than other fly species. Secondly, tsetse fly males appear to actually defy the norm for r-type strategists, who ordinarily prioritize quantity over quality, by inhibiting the females’ ability to mate more than once, ensuring that a male’s one-night-stand with a female is the first and last time that female will ever mate! At first, one might be stunned to hear this and ask, “Why would a species, especially of the r-type strategist variety, limit its own reproductive capability? Even K-type strategists will typically mate multiple times and with multiple partners throughout their lives!” To answer this question, let us take a closer look:

If Aristotle were alive today, he might, as he did with other critters in Generations of Animals, write that the telos of the tsetse fly’s viviparity (trait for giving live birth), while reducing the quantity of offspring that can be had, serves the benefit of shielding the larvae from parasites that they would be vulnerable to if left unattended in eggs. But what of a male’s ability to inhibit a female’s ability to mate more than once? For starters, let us acquire some additional context: As mentioned, female tsetse flies will only give birth ten times, and this is regardless of who they mate with. If they mate with a single male one time, then they will continue using that same male’s sperm for the rest of their life. However, the first male that a female mates will inject her with a substance that shuts down her sex drive forever, meaning she will never desire to mate again—not even again with her first partner. Aristotle might have asserted that shutting off the female tsetse fly’s sex drive would cause her to spend less energy mating and more energy incubating her fetuses, and thus is beneficial for future generations in an environment where resource and energy consumption is a critical limiting factor. This proposition would assert part of the position that I uphold: that environmental pressures (in this case, available resources and energy) are the arbiter, and that reproduction is a “final cause” or teleological end of evolution itself.

One could, however, counter and assert the individualist point of view, saying that this is the male’s way of ensuring his own genes are more likely to pass on versus the genes of other males. But this would imply a conscious Lamarckianism, as if the male “knows” that he has the ability to block out other males from reproducing with a given female and has “willed” this ability into existence. But this is clearly rubbish; organisms cannot acquire such advanced mutations through epigenetic changes experienced in their own lifetime (and certainly not on demand), and the fly does not possess the intellectual capacity to consider the fate of his own genes through his reproductive efforts and sustainment in his progeny.

So let us try some other approaches: We might imagine that early on in the tsetse fly’s evolution that some females mated with males who did not possess an “exclusivizing gene”, while others did. Perhaps the exclusivizing gene spread passively because there were no environmental pressures to stop it (a neutral trait), or perhaps it spread because females who diverted more energy toward incubating offspring than to mating multiple times, were more successful in carrying these offspring to term, and these offspring would then grow up and spread that same gene. We might also think of it mathematically, in that the males who carried the exclusivizing gene would produce up to ten times as many offspring through a mate compared to individual males who did not carry this gene (assuming that early on the female could make use of more than one male’s sperm), and thus the competitive edge for this gene would be 10:1 in favor of the carriers.

These explanations may give us some insight into how the trait potentially spread, and thus they answer the efficient cause of the trait’s propagation (i.e., they inform us of the conditions under which this trait came to be prevalent in the species), but what they neglect is the final cause. That is, “why” is it “good” that this trait came about and spread in the first place? One might attempt, again, to invoke the individualist perspective, but that would merely return us to the flaw in asserting a “conscious Lamarckianism”. One might say that this trait is purely neutral and arose haphazardly, like blindness in blind deepwater fish, but a trait so complex that it arms males with an injectable chemical anaphrodisiac (sex drive suppressant) with a permanent lasting effect, is certainly not some simple mutation which could come about in a single generation. Rather, it is a very complex and functionally “new” trait (that is, it is not a modification or variation of an existing trait, like how blindness is a variation of sight capacity) which would require many generations to fully evolve and develop. So how did it arise in the first place? Why was it worked toward over several generations? What was particularly “good” about it?

Determining and recognizing the final cause here is critical. If evolution is a non-teleological process as the accidentalists proport, then they must contend with the above questions: “Why was it worked toward over several generations? What was particularly ‘good’ about it?” Thus, our focus is no longer strictly of a materially scientific concern, but of philosophical concern. And the only reliable way to answer these questions, it would seem, would be to assert a teleology for the process. In fact, by asking “why” in the first place, we are automatically invoking a discussion on telos; it is presumed in the question itself. There must be a “goodness”, or something “good”, about the evolved condition of the tsetse flies, which would imply that something has “deemed” this status good. Now, following what I have argued previously, that which “deems” this status good would be in some way the environment which has “demanded” evolutionary changes in the first place. But this trait of the flies we speak of is so complex that we cannot relegate it to just the environment in the mundane sense; we have to think bigger, on to the whole of Reality itself!

To avoid sounding like a creationist who speaks of an “Intelligent Designer” in extrinsic fashion, let us take the intrinsic approach, by saying that the “design” of the organism in its present state is simply descriptive of a deterministic reality. (And here, I do not mean to use the word “deterministic” as if in relation to the type of determinism exercised in the deliberation of an extrinsic volition or telos, but rather I say “determinism” to indicate a condition which is descriptive of Reality as it is.) In fact, it might best be worded that the “Providence” at play is Determinism with a capital D—a “preordaining” of the features of Reality. If the accidentalist might excuse the use of religious language, my friend Praxius has a good way of thinking about this in his essay, The Verticality of God’s Plan:

“Indeed, often God’s Plan is thought to refer to a temporally linear series of events over which we have little effect, or, in other words, to a purely temporal predestination and positive fatalism. In this context, God’s Plan is often spoken of positively, not simply in its affirmation, but as a comfort to those upon whom some misfortune or another has fallen, and therefore its insinuation of a ‘positive end’, so to speak, has the same effect on those of a religious persuasion as nihilism does on the atheist. Our understanding of this conception is quite different. In the common understanding, the word ‘plan’ can be defined as ‘the will and intention to carry out a particular action or series of actions’, and in this regard the word carries a temporal connotation; for us, the word ‘plan’ equates to the word ‘design’, which refers to requirements to be satisfied and/or conditions to be met, and in this regard the word carries an atemporal or principled definition.”

To apply this to our discussion on evolution, what has “deemed” the goodness of the organism’s present state, and its evolution toward this state over time, is simply “the will and intention to carry out a particular action or series of actions”, which is descriptive of the automatic, deterministic, or preordained “Design” of Reality itself. This is what I reify as “Providence”. If “Providence”, whether taken literally or metaphorically, signifies “God”, the agency or volition of God is then simply an “aboutness” to Reality—an expression of Reality’s metaphysical normativity or “ontological propriety”, as is discussed in my other two essays, Finding God in the Void and Beyond Politics: Defining the True Right.

Chapter 3, Part C: Implications: Tying it All Together

As discussed in the previous part of this chapter, what we see in both the acts of “jumping” and especially in convergent evolution is more or less a “creative awareness” or Providential “Determinism” that characterizes evolutionary processes, much like that which might arguably be said to govern all mundane physical processes (as all of primary features of reality might be said to be preordained or “designed” in some automatic or deterministic fashion), but with a certain heightened degree of obviosity present in the bio-evolutionary sphere. The very “cobbl[ing] together of design solutions” or even the preconceived “destiny” of a species which goes extinct or succumbs to dysgeny, which accidentalists speak of, is in essence what we call Providence, regardless of whether one wants to assign it such a reification or religious connotation. It is, most simply, telos. Every reification one can assign is just an alternative vocabulary for “telos” or “final cause”.

“But I thought we were not supposed to conflate the process of evolution with the final cause?” Ah, first off, I would like to congratulate you for paying attention if this was your thought. The fourth perspective I am presenting here, namely that there is some “guiding hand” involved (even if like Aristotle we choose to believe that there is no God acting here), is not one which seeks to conflate the efficient cause (evolution as a process) with the final cause (its ends), but merely to express an extricable interconnectedness between them: Namely, that the process is only permitted insofar as it is given something to work toward. Think of carpentry, for instance. In nature, wood is never compelled to bridge impossible gaps in transformation and assume the shape of chairs or desks. Yet a designated actor or agent of change (the carpenter) conducts the process of carpentry (the efficient cause), with the intent of producing a finished product (the final cause). In much the same way, Providence is not only the source of a species’ “destiny”, but is the very “guiding hand” which permits it to bridge impossible gaps. And again, the usage of such terms as “guiding hand” is only for the sake of reification. I am not demanding that anyone should profess a religious faith; I merely seek to emphasize the necessity of a final cause or telos in the equation.

Additionally, in embracing Providence, we find in this approach that the environmental pressures exerted on organisms, while significant, operate within the context of their final ends. Moreover, it is not merely the environment, but the structure of Reality itself at play. That is, we might say that organisms are predisposed toward predetermined ends according to their setting (which has been “preordained”), such that new “innovations” in evolution—like the combined urinary/genital junction of mammals or the tsetse fly’s anaphrodisiac—are “determined” to be what is “good” for that species in response to the relevant imposing environmental pressures which are relegated “down” by the “Design” of Reality. (This is in much the same way that something was “good” about Socrates’ choice to sit in prison as opposed to stand.) A “determination”, for lack of a better term, “wills”, “establishes”, or “preordains” the final cause (even if only in a purely intrinsic manner).

End Note

I hope I have been successful in satisfying the goal that this essay set out to accomplish. Thank you for reading.

"We find often that despite the accidentalists’ attempts to deny the metaphysical, boiling everything down to materialism or physicalism, and accidentalism, that they often cannot shake a sense of fulfilment or purpose which manifests as the desire for starting a family, for having a spouse and children. The accidentalists, however, might contend that this desire, like every emotion, in the eliminationist sense is but an illusion, reducible to some chemical reaction in their brain that natural selection has “deemed” or “found” beneficial to the survival of the human species."

SCIENCE! lovers have gone insane! I know you're not a dualist, but I reckon a lot of their apprehension towards assigning a scheme to evolution has to do with an interest in subjugating the metaphysical to the physical. If, after all, the metaphysical is not purely derived from the human consciousness (which SCIENCE! lovers usually explain away as itself also ultimately physical, just also uniquely complex) and has an accredited, manifest pre-existence, it calls into question the source (or rather, Source) of this phenomena, including the "gravitational" mechanisms of evolution. But otherwise, I loved seeing a post this exhaustive on this subject; even reminds me of this article from a few years back - https://lukesmith.xyz/articles/we-want-our-4-causes-back/